“…de propriedades quase musicais, no espaço em que se movem os viventes”.

“…DE PROPRIEDADES QUASE MUSICAIS, NO ESPAÇO EM QUE SE MOVEM OS VIVENTES”.

Paul Valéry

Fernando Cocchiarale, Novembro, 2016

Sobre a construção de “propriedades quase musicais, no espaço em que se movem os viventes”.

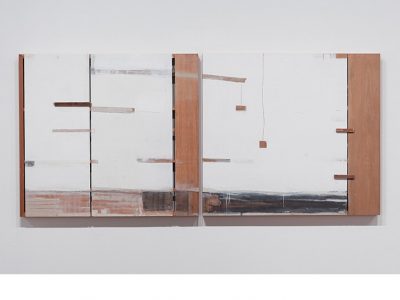

A exposição “… de propriedades quase musicais, no espaço em que se movem os viventes” (título extraído por Ana Muglia de trecho de Eupalinos ou O Arquiteto, de Paul Valéry) é, segundo declaração da própria artista, “uma mostra de pintura em madeira de grandes formatos, série de desenhos sobre tela crua em pequenos formatos, algumas folhas do Caderno de artista sobre suporte de madeira e base de concreto e um vídeo, cujo foco é trabalhar as semelhanças visuais e rítmicas entre o espaço da construção arquitetônica e o da estrutura musical”.

Os diferentes meios técnicos utilizados por Muglia nesses trabalhos nos remetem às categorizações convencionais que traçavam, até recentemente, as fronteiras entre pintura, desenho e escultura.

Nesse sentido, destacamos trechos de seu depoimento que, direta ou sutilmente, evidenciam o fio condutor pictórico que atravessa o conjunto de sua produção: “uma mostra de pintura em madeira de grandes formatos”, “desenhos sobre tela crua”, “Caderno de artista sobre suporte de madeira” e vídeo sobre “semelhanças […] entre o espaço da construção arquitetônica e o da estrutura musical”.

Mas para a compreensão do sentido poético específico dessa pintura de Muglia que transborda os limites convencionais entre desenho, escultura e música é necessário averiguar tanto o sistema pictórico que norteia sua fatura (a escolha dos materiais de que são construídas e que as estruturam), quanto confrontá-la com questões pictóricas e poéticas formuladas pela arte moderna e por seus desdobramentos na produção contemporânea.

A redução da pintura aos seus atributos objetivos essenciais, concentrada na reiterada afirmação do plano pictórico (oposto à representação naturalista e ao ilusionismo permitido pela perspectiva e pelo sombreado que a marcaram entre a Renascença e a modernidade) deixou clara a importância do suporte ou das superfícies em que eram pintadas.

Tais suportes conectavam a atividade pictórica propriamente dita à superfície de um plano materialmente objetivo. Era necessário vencê-lo para a o triunfo da simulação do espaço (ou da cena) que acolhia a representação. Pinturas seriam, então, inseparáveis dos diferentes espaços que as acolheram e as perenizaram milhares de anos antes da invenção da escrita, portanto, antes de qualquer narrativa histórica. Dentre esses suportes, destacam-se a parede (de cavernas, templos e palácios) e, mais recentemente, a tela e o papel.

Foi somente a partir da segunda metade do século XIX, com a formação das primeiras vanguardas europeias, que a materialidade planar do suporte pictórico se generalizou para consolidar a modernidade aspirada. A produção artística, entretanto, continuou a explorar e a aprofundar novas possibilidades poéticas inauguradas pela investigação do plano pictórico.

Já na segunda metade dos anos cinquenta, Lucio Fontana, na série de pinturas Concetto spaziale, começou a fazer incisões com navalhas ou tesouras sobre telas monocromaticamente pintadas.

As incisões de Fontana nos revelavam de imediato que, ao contrário do conceito teórico de plano (Euclides), o plano pictórico – tela − possuía concretamente uma fina espessura: um outro lado que confinava com a parede sobre a qual o quadro era situado. Havia aqui uma crítica à “dimensão planar” que celebrava a superfície do suporte da pintura modernista, destinada à composição.

Muglia ultrapassa o debate sobre o plano pictórico para extrair das entranhas da parede, invisíveis ao olhar fruidor e à compreensão habitual, a organização material, espacial e cromática de seus trabalhos. É, portanto, uma pintura de afloramento, que reconstrói tais entranhas na superfície dos trabalhos. Finalmente é preciso esclarecer que diferentemente do construtivismo histórico, baseado em noção de estrutura análoga à da engenharia do ferro, as construções da artista exploram, sobretudo, a potência pictórica dos materiais por ela apropriados da construção civil brasileira (de onde extrai a sutil precariedade de sua pintura).

“…ALMOST MUSICAL PROPERTIES, IN THE SPACE WHERE THE LIVING MOVE”.

Paul Valéry

Fernando Cocchiarale, November, 2016

On the construction of “almost musical properties, in the space where the living move.”

The exhibition entitled “… of almost musical properties, in the space where the living move” (extracted by Ana Muglia from Eupalinos or the Architect, by Paul Valéry) is, according to the artist herself, “an exhibition of large-scale painting on wood, a series of small drawings on raw canvas, a few leafs from the Artist’s Notebook on a wooden support and concrete base, and a video whose focus is to investigate the visual and rhythmic similarities between the space of architectural construction and that of musical structure.”

The different technical means Muglia uses in these works remind us of the conventional categories that until recently marked the dividing lines between painting, drawing, and sculpture.

With this in mind, we highlight some passages from her testimonial, which directly or implicitly indicate the pictorial thread that runs through her body of work: “an exhibition of large-scale painting on wood,” “drawings on raw canvas,” “the Artist’s Notebook on a wooden support,” and a video about “similarities […] between the space of architectural construction and that of musical structure.”

But to understand the specific poetic meaning of this painting of Muglia’s, which transcends the conventional boundaries between drawing, sculpture, and music, it is necessary to ascertain the pictorial system upon which it is based (the choice of the materials it is made from and that structure it) and to contrast it with poetic and pictorial questions formulated by modern art and its ramifications in contemporary output.

The reduction of painting to its essential objective attributes, concentrated in the repeated affirmation of the pictorial plane (as opposed to naturalist representation or the illusionism permitted by the perspective and shading that marked it from the Renaissance to modernity), evinced the importance of the supports or surfaces on which it was painted.

These supports connected pictorial activity per se with the surface of a materially objective plane. It was necessary for this to be overcome before the simulation of the space (or setting) that harbored representation could be attained. This meant paintings would be inseparable from the different spaces they belonged to and which had allowed them to last thousands of years before the invention of writing, and thus before any historical narrative. Chief amongst these supports were walls (caves, temples, palaces) and, more recently, canvas and paper.

It was only as of the mid-1800s, with the emergence of the first European vanguards, that the plane materiality of the pictorial support became widespread in the consolidation of sought-after modernity. However, artists continued to explore and probe the new poetic possibilities thrown up by the investigation of the pictorial plane.

In the mid-1950s, Lucio Fontana, in his series of paintings called Concetto Spaziale, started to slash painted monochrome canvasses with blades or scissors.

Fontana’s incisions immediately showed us that unlike the theoretical concept of the plane (Euclid), the pictorial plane – the canvas – actually had thickness: another side closed against the wall on which the painting was hung. They contained a criticism of the “plane dimension” that celebrated the surface of the support in modernist painting, destined for composition.

Muglia goes beyond the debate about the pictorial plane to extract from the entrails of the wall, invisible to the receiving gaze and habitual comprehension, the material, spatial, and chromatic organization of her works. This is therefore a painting of outcrops that reconstructs these entrails on the surface of the works. Finally, we must clarify that unlike the historical constructivists, drawing on a notion of structure analogous to that of ironwork, Muglia’s constructions explore above all the pictorial potency of the materials appropriated by her from Brazilian civil construction (from which she extracts the subtle precariousness of her painting).